The Walls

The Castelo de São Jorge is part of an extensive and ancient defensive system which stands imposingly atop a hill overlooking the Tagus River.

The first known written record about this fortification dates back to 985 AD. It comes in the form of an Arabic epigraph which testifies to the repairing of the city wall during the time of Hišām II, under the patronage of the famous governor of the Al-Andaluz and great military man, Almançor.

This epigraph (a Roman stele reused in the Islamic period) was found in 1939 between two towers in the western area of Castelo de S. Jorge and is on display in the Museu da Cidade.

It was likely built into the wall or over a doorway.

The construction works documented in the epigraph, as well as the descriptions of geographers and reports of 12th-century crusaders,

confirm that this was a walled city which extended down to the river, with a citadel positioned at the very top of the hill and encircled by walls.

The Castelo de São Jorge is part of an extensive and ancient defensive system which stands imposingly atop a hill overlooking the Tagus River.

It is possible that pre-Roman Lisbon was protected by a wall (as many other Iron Age settlements in the west of the peninsular were), but no real evidence for this has thus far been found.

The oldest defensive walls identified in Lisbon date back to the Roman period and suggest a city that stretched from the top of the hill down to the riverside. It appears that it was limited to the west by the tidal creek of the baixa area and to the east by a topography of very steep slopes.

Although we have a relatively good understanding of the layout of these walls (from the Imperial period and later) to the east and the south, their northern limit, in the area where the castle is located, remains unknown

As such, we know that part of the Islamic wall lies within the perimeter of the national monument, specifically the wall of the alcaçova (casbah or citadel). At the time, this is the area where the political, military and religious elites would have resided.

The first known written record about this fortification dates back to 985 AD. It comes in the form of an Arabic epigraph which testifies to the repairing of the city wall during the time of Hišām II, under the patronage of the famous governor of the Al-Andaluz and great military man, Almançor.

This epigraph (a Roman stele reused in the Islamic period) was found in 1939 between two towers in the western area of Castelo de S. Jorge and is on display in the Museu da Cidade.

It was likely built into the wall or over a doorway.

The construction works documented in the epigraph, as well as the descriptions of geographers and reports of 12th-century crusaders, confirm that this was a walled city which extended down to the river, with a citadel positioned at the very top of the hill and encircled by walls.

This fortress was conquered by Afonso Henriques, the first king of Portugal, in 1147.

Later, King Ferdinand decided to extend the city walls to the east and the west of the Old Wall and Moorish Wall in order to protect the expanding city.

This new wall, built in 1373, had 46 gateways and 77 towers

Where the west and the south walls of the Castelo de S. Jorge meet, a section of the wall descends down the hillside in a south-westerly direction, towards St. Lawrence’s Tower which protected a gateway which has since disappeared.

This section of wall and the section which delimits part of the Praça Nova (New Square), were part of the construction works undertaken by King Ferdinand with the aim of expanding Lisbon and strengthening its defences.

This new ring of walls is commonly known as the Fernandine Wall, named after the monarch who undertook its construction.

- Porta de S. Jorge (St. George’s Gate)

- Porta do Espírito Santo (Gate of the Holy Spirit)

- Porta de Santa Cruz (Gate of Santa Cruz)

- Porta Norte (North Gate)

- Porta do Moniz (Moniz Gate)

© Sergiy Scheblykin

This was the main gateway into the enclosure of the citadel, which originally would have been located slightly higher up than the current one.

Its oldest iconographic depiction dates back to the 16th century.

It began to be rebuilt in 1831 and was only completed 15 years later during the reign of Queen Mary II.

The gateway consists of a round arch, decorated with marble which belonged to one of the chapels at the Convento dos Lóios and is topped by a stone bearing the royal coat of arms.

The inscription 4 / 4º / 1846 / D. Maria II is still preserved on the arch’s keystone, and on the outer walls are other inscriptions dedicated to the Duke of Terceira and the Count of Tomar.

© Sergiy Scheblykin

A pointed-arch gateway with bevelled edges and the armillary sphere of King Manuel (1495-1521) at its apex. On the walls either side of the gateway are loopholes and to the left, on the exterior face of the wall, is the coat of arms of King Afonso III.

© Sergiy Scheblykin

Porta de configuração ogival e de arestas biseladas rematada por pedra armoriada real, seiscentista.

It is located next to the Archaeological Centre (Praça Nova) and provides access to the Church of Santa Cruz.

This church was erected during Afonso Henriques’ reign on top of an old mosque. Destroyed by the earthquake, it was rebuilt in 1776. The bell tower of the church is actually a repurposed tower belonging to the castle wall.

© Sergiy Scheblykin

This gate is located in the northern section of the wall, near where it meets the northeast point of the castle, next to the Cistern Tower.

The round-arch gateway was discovered and uncovered during the building works of 1939.

It seems this was an important access point on this side of the fortress which probably led to a road, now disappeared, which connected the citadel to the city’s northern outskirts.

It is one of the gateways into the citadel.

© Kenton Thatcher

The Moniz Gate is an old gate of the Moorish Wall and one of the gateways leading to Castelo de São Jorge’s Praça Nova.

It is associated with a legend praising the feat of a Portuguese knight called Martim Moniz. According to the legend, he allowed the Portuguese army to enter the fortress by using his body to keep the wooden gates of this entrance open, sacrificing his own life in the process.

This narrative which was, without doubt, part of the collective memory, is today very difficult to prove and has been contested by many historians.

Nevertheless, the Moniz Gate was already going by this name in a scripture from the tomb in the Church of Santa Cruz do Castelo, which dates from 1258.

Who was Martim Moniz?

© Kenton Thatcher

Son of a man named Monio possibly Monio Osorez de Cabrera and Maria Nunes de Grijó. Martim is thought to have married Teresa Afonso, who some genealogists believe was the illegitimate daughter of King Afonso Henriques.

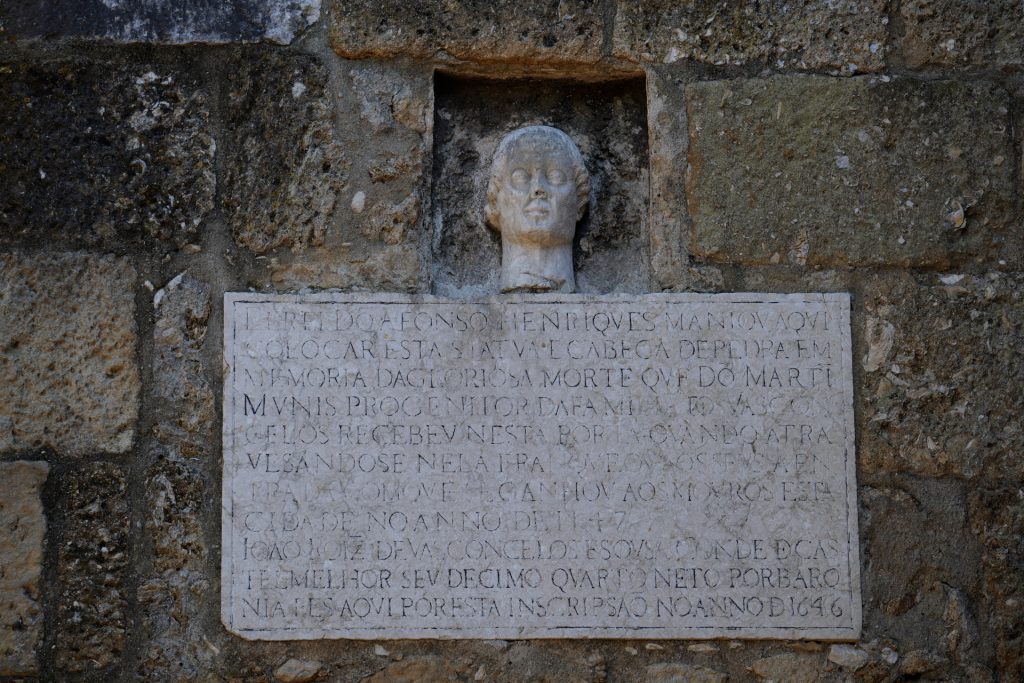

In the second half of the 17th century and with the advent of a new dynasty bringing to an end Castilian rule, the castle played a central role in the mythicised propaganda of a Portugal glorified through its heroes and moments of glory. As Martim Moniz was considered the progenitor of the Vasconcelos family, his assumed descendent João Rodrigues de Vasconcelos e Sousa (a prominent figure during the Restoration of Portuguese Independence) had a plaque placed over the gateway, which reads:

KING AFONSO HENRIQUES ORDERED THAT THIS STONE STATUE AND HEAD BE PLACED HERE IN MEMORY OF THE GLORIOUS DEATH THAT DO[M] MARTI[M] MONIS, PROGENITOR OF THE VASCONCELOS FAMILY, RECEIVED WHEN CROSSING THROUGH THIS GATE AND ALLOWING HIS COMPANIONS TO GAIN ENTRY, WHICH WON THE CITY BACK FROM THE MOORS IN THE YEAR 1147.

JOÃO ROIZ DE VASCONCELOS E SOUSA COUNT OF CASTEL MELHOR, HIS FOURTEENTH GRANDSON, BY BARONY, MADE THIS INSCRIPTION IN THE YEAR 1646.

In a niche above the memorial stone, there is a marble bust depicting Martim Moniz. We are uncertain when it was placed here.